THE FIRST WOMAN CANDIDATE FOR U.S. PRESIDENT: VICTORIA WOODHULL

Major Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Victoria_Woodhull

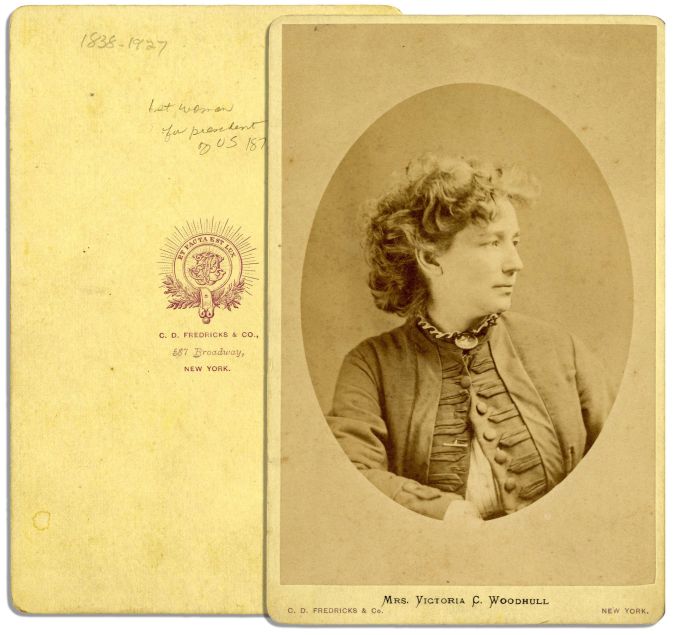

Victoria Woodhull by CD Fredericks. circa 1870

Victoria Woodhull was the first woman to run for President of the United States in 1872. An activist for women’s rights and labor reforms, Woodhull was also an advocate of free love. She believed women should be free to to marry, divorce, and bear children without government interference.

Woodhull was politically active in the early 1870s, when she was nominated as the first woman candidate for the United States presidency, for which she is best known.

Woodhull was the 1872 candidate for the Equal Rights Party, who supported women’s suffrage and equal rights. She was arrested on obscenity charges a few days before the election, for publishing an account of the alleged adulterous affair between the prominent minister Henry Ward Beecher and Elizabeth Tilton. This bit of red meat added to the sensational coverage of her candidacy. Though she was on the ticket, she did not receive any electoral votes, and there is conflicting evidence about popular votes.

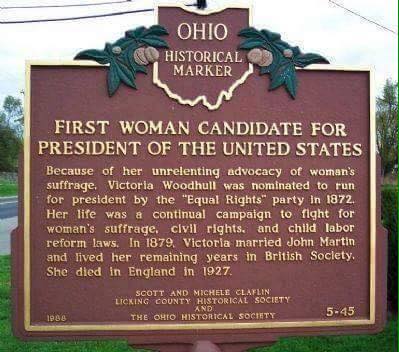

Licking County, Ohio Historical Sign

EARLY LIFE AND EDUCATION

Born Victoria California Claflin, she was the seventh of ten children (six of whom survived to maturity),in the rural frontier town of Homer, Licking County, Ohio.

“Her mother, Roxanna “Roxy” Hummel Claflin, was illegitimate and illiterate. She had become a follower of the Austrian mystic Franz Mesmer and the new spiritualist movement. Her father, Reuben “Old Buck” Buckman Claflin, was a con man and snake oil salesman. He came from an impoverished branch of the Massachusetts-based Scots-American Claflin family, semi-distant cousins to Governor William Claflin. -Wikipedia

When seven years old, Victoria was accused of burning down a cupola.

She was beaten, starved and sexually abused by her father when still very young.

She believed in spiritualism – she referred to “Banquo’s Ghost” from Shakespeare‘s Macbeth – because it gave her belief in a better life. She said that she was guided in 1868 by Demosthenes to what symbolism to use supporting her theories of Free Love.

By age 11, Woodhull had only three years of formal education, but her teachers found her to be extremely intelligent. She was forced to leave school and home with her family when her father, after having “insured it heavily,” burned the family’s rotting gristmill. When he tried to get compensated by insurance, his arson and fraud were discovered; he was run off by a group of town vigilantes. The town held a “benefit” to raise funds to pay for the rest of the family’s departure from Ohio.

FREE LOVE

VICTORIA WOODHULL caricature by Thomas Nash, 1872.

Woodhull’s support of free love likely started after she discovered the infidelity of her first husband Canning Woodall. Shortly after their marriage she learned that her new husband was an alcoholic and a womanizer.

Women who married in the United States during the 19th century were bound to their unions, even if loveless, with few options to escape. Divorce was limited by law and considered socially scandalous. Women who divorced were stigmatized and often ostracized by society. Victoria Woodhull concluded that women should have the choice to leave unbearable marriages.

Woodhull believed in monogamous relationships, although she also said she had the right to change her mind: the choice to make love or not was in every case the woman’s choice (since this would place her in an equal status to the man, who had the capacity to rape and physically overcome a woman, whereas a woman did not have that capacity with respect to a man).[17]

Woodhull said: “To woman, by nature, belongs the right of sexual determination. When the instinct is aroused in her, then and then only should commerce follow. When woman rises from sexual slavery to sexual freedom, into the ownership and control of her sexual organs, and man is obliged to respect this freedom, then will this instinct become pure and holy; then will woman be raised from the iniquity and morbidness in which she now wallows for existence, and the intensity and glory of her creative functions be increased a hundred-fold . . .”

In this same speech, which became known as the “Steinway speech,” delivered on Monday, November 20, 1871 in Steinway Hall, New York City, Woodhull said of free love: “Yes, I am a Free Lover. I have an inalienable, constitutional and natural right to love whom I may, to love as long or as short a period as I can; to change that love every day if I please, and with that right neither you nor any law you can frame have any right to interfere.”

Woodhull railed ag

Victoria Woodhull by Bradley and Rulofson

ainst the hypocrisy of society’s tolerating married men who had mistresses and engaged in other sexual dalliances. In 1872, Woodhull publicly criticized well-known clergyman Henry Ward Beecher for adultery. Beecher was known to have had an affair with his parishioner, Elizabeth Tilton, who had confessed to it, and the scandal was covered nationally. Woodhull was prosecuted on obscenity charges for sending accounts of the affair through the federal mails, and was briefly jailed. This added to sensational coverage during her campaign that fall for the United States presidency.

PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATE

Woodhull announced her candidacy for President by writing a letter to the editor of the New York Herald on April 2, 1870.

Woodhull was nominated for President of the United States by the newly formed Equal Rights Party on May 10, 1872, at Apollo Hall, New York City. A year earlier, she had announced her intention to run. Also in 1871, she spoke publicly against the government being composed only of men; she proposed developing a new constitution and a new government. Her nomination was ratified at the convention on June 6, 1872. They nominated the former slave and abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass for Vice President. He did not attend the convention and never acknowledged the nomination. He served as a presidential elector in the United States Electoral College for the State of New York. This made her the first woman candidate.

While many historians and authors agree that Woohull was the first woman to run for President of the United States, some have questioned that priority given issues with the legality of her run. They disagree with classifying it as a true candidacy because she was younger than the constitutionally m

Victoria Woodhull by Mathew Brady, c1870

andated age of 35. However, election coverage by contemporary newspapers does not suggest age was a significant issue. The presidential inauguration was in March 1873. Woodhull’s 35th birthday was in September 1873.

Woodhull’s campaign was also notable for the nomination of Frederick Douglass, although he did not take part in it. His nomination stirred up controversy about the mixing of whites and blacks in public life and fears of miscegenation (especially as he had married a much younger white woman after his first wife died).

Frederick Douglass, the famed civil rights activist, was nominated to be her vice president, though he never acknowledged or accepted the nomination publicly. But while historians look back as Woodhull’s nomination as an historic first, her long-shot candidacy caused her serious trouble as soon as the nominating convention was over, Richman and Freemark report.

“As a result of the notoriety of the nomination, Woodhull was evicted from her home and she had some trouble making ends meet,” [biographer Amanda] Frisken tells [reporters Joe] Richman and [Samara] Freemark. Woodhull’s family was forced to sleep in her brokerage office for a period of time, as New York landlords were unwilling to rent to her, Kate Havelin writes in her book, Victoria Woodhull: Fearless Feminist. Woodhull’s 11-year-old daughter, Zula, meanwhile, had to leave her school as other parents didn’t want Zula to influence their children.

The Equal Rights Party hoped to use the nominations to reunite suffragists with African-American civil rights activists, as the exclusion of female suffrage from the Fifteenth Amendment two years earlier had caused a substantial rift between the groups

Having been vilified in the media for her support of free love, Woodhull devoted an issue of Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly (November 2, 1872) to an alleged adulterous affair between Elizabeth Tilton and Reverend Henry Ward Beecher, a prominent Protestant minister in New York (he supported female suffrage but had lectured against free love in his sermons). Woodhull published the article to highlight what she saw as a sexual double-standard between men and women.

Having been vilified in the media for her support of free love, Woodhull devoted an issue of Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly (November 2, 1872) to an alleged adulterous affair between Elizabeth Tilton and Reverend Henry Ward Beecher, a prominent Protestant minister in New York (he supported female suffrage but had lectured against free love in his sermons). Woodhull published the article to highlight what she saw as a sexual double-standard between men and women.

JAILED BEFORE CONVENTION

That same day, a few days before the presidential election, U.S. Federal Marshals arrested Woodhull, her second husband Colonel James Blood, and her sister Tennie C. Claflin on charges of “publishing an obscene newspaper” because of the content of this issue.[32] The sisters were held in the Ludlow Street Jail for the next month, a place normally reserved for civil offenses, but which contained more hardened criminals as well.

The arrest was arranged by Anthony Comstock, the self-appointed moral defender of the nation at the time. Opponents raised questions about censorship and government persecution. The three were acquitted on a technicality six months later, but the arrest prevented Woodhull from attempting to vote during the 1872 presidential election. With the publication of the scandal, Theodore Tilton, the husband of Elizabeth, sued Beecher for “alienation of affection.” The trial in 1875 was sensationalized across the nation, and eventually resulted in a hung jury.

Woodhull again tried to gain nominations for the presidency in 1884 and 1892. Newspapers reported that her 1892 attempt culminated in her nomination by the “National Woman Suffragists’ Nominating Convention” on 21 September. Mary L. Stoweof California was nominated as the candidate for vice president. The convention was held at Willard’s Hotel in Boonville, New York, and Anna M. Parker was its president. Some woman’s suffrage organizations repudiated the nominations, however, claiming that the nominating committee was unauthorized. Woodhull was quoted as saying that she was “destined” by “prophecy” to be elected president of the United States in the upcoming election.

VIEWS ON ABORTION AND EUGENICS

Her opposition to abortion is frequently cited by opponents of abortion when writing about first wave feminism. The most common Woodhull quotations cited by opponents of abortion are: “the rights of children as individuals begin while yet they remain the fetus.”

“Every woman knows that if she were free, she would never bear an unwished-for child, nor think of murdering one before its birth.”

One of her articles on abortion not often cited by opponents of abortion is from the September 23, 1871 issue of the Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly. She wrote: “Abortion is only a symptom of a more deep-seated disorder of the social state. It cannot be put down by law… Is there, then, no remedy for all this bad state of things? None, I solemnly believe; none, by means of repression and law. I believe there is no other remedy possible but freedom in the social sphere.”

Woodhull also promoted eugenics which was popular in the early 20th century prior to World War II. Her interest in eugenics might have been motivated by the profound intellectual impairment of her son. She advocated, among other things, sex education, “marrying well,” and pre-natal care as a way to bear healthier children and to prevent mental and physical disease. Her writings demonstrate views closer to those of the anarchist eugenists, rather than the coercive eugenists like Sir Francis Galton.

In 2006, publisher Michael W. Perry claimed in his book “Lady Eugenist” that Woodhull supported the forcible sterilization of those she considered unfit to breed. He based his claim on a New York Times article from 1927 in which she concurred with the ruling of the case Buck v. Bell. Whether the article accurately stated her views or not, it stands in stark contrast to her earlier works in which she advocated social freedom and opposed government interference in matters of love and marriage.

Other women, including Belva Lockwood, have launched runs for the presidency since, but nearly a century passed between Woodhull’s run and the first woman to vie for the nomination of a major party. Maine Sen. Margaret Chase Smith tried in vain for the Republican nomination in 1964; New York Rep. Shirley Chisholm tried for the Democratic nomination in 1972, as did Rep. Patsy Mink from Hawaii. In more recent years, Colorado Rep. Patricia Schroeder, cabinet secretary and later North Carolina Sen. Elizabeth Dole, Illinois Sen. Carol Moseley Braun, and Minnesota Rep. Michele Bachman would compete for the nomination of the Republican or Democratic parties. It is, when one thinks about it, astonishing that a woman, in a country in which women are the majority of voters, has never been the nominee of either major party. And in 2016, with some 20 competitors for the Republican nomination, all but one—extreme long shot Carly Fiorina—are men.

ADDITIONAL SOURCES:

Felsenthal, Carol. “The Strange Tale of the First Woman to Run for President.” Politico. 5 April 2015.

Greenspan, Jesse: “9 Things You Should Know About Victoria Woodhull.”

History. 23 September 2013.

LaGanga, Maria L: “Women Who Ran Before Hillary Clinton: ‘I Cannot Vote, But I Can Be Voted For.'” The Guardian. 8 June 2016.

Lewis, Danny: “Victoria Woodhull Ran for President Before Women Had the Right to Vote.” Smithsonian SmartNews. 10 May 2016.

REFERENCES:

1 Kemp, Bill (2016-11-15). “‘Free love’ advocate Victoria Woodhull excited Bloomington”. The Pantagraph. Retrieved 2016-04-13.

The Revolution, a weekly newspaper founded by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, had begun publication two years earlier in 1868.

Goldsmith, Barbara (1998). Other Powers. Alfred A. Knopf. p. 20. ISBN 0394555368.

1850 federal census, Licking, Ohio; Series M432, Roll 703, Page 437; father listed as Buckman, brothers incorrectly transcribed as Hubern (Hubert) and Malven (Melvin).

Wight, Charles Henry, Genealogy of the Claflin Family, 1661–1898. New York: Press of William Green. 1903. passim (use index)

Gabriel, Mary (1998). Notorious Victoria. Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. p. 12. ISBN 1-56512-132-5.

“Ohio, County Marriages, 1789-2013, index and images, FamilySearch “Marriage records 1849-1854 vol 5 > image 273 of 334; county courthouses, Ohio”. familysearch.org. Retrieved 2015-06-09.

Underhill, Lois Beachy (1996). The Woman Who Ran for President: The Many Lives of Victoria Woodhull. Penguin Books. p. 24. ISBN 0-14-025638-5.

“Woodhull, Zula Maude”. Who’s Who. 59: 1930. 1907.

Dubois and Dumenil, //Through Women’s Eyes: An American History with Documents//. (Bedford; St. Martin’s, 2012)

“And the truth shall make you free.” A speech on the principles of social freedom, delivered in Steinway hall, Nov. 20, 1871, by Victoria C. Woodhull, pub. Woodhull & Claflin, NY, NY 1871. [1]

Speech is discussed and linked to also in Shearer, Mary L. “Abandoned Woman? A Review of the Evidence.” http://www.victoria-woodhull.com/prostitute.htm

DuBois and Dumenil. //Through Women’s Eyes: An American History with Documents//. (Bedford; St Martin’s, 2012)

Shearer, Mary L. “Frequently Asked Questions about Victoria Woodhull.” http://www.victoria-woodhull.com/faq.htm#who

Susan Kullmann, “Legal Contender… Victoria C. Woodhull, First Woman to Run for President”. Accessed 2009.05.29.

Messer-Kruse, Timothy (1998). The Yankee International: Marxism and the American Reform Tradition, 1848–1876. pp. 2–4.

“Notes on the “American split””. May 28, 1872. Retrieved 2010-08-05.

A Lecture on Constitutional Equality, also known as The Great Secession Speech, speech to Woman’s Suffrage Convention, New York, May 11, 1871, excerpt quoted in Gabriel, Mary, Notorious Victoria: The Life of Victoria Woodhull, Uncensored (Chapel Hill, N.Car.: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 1st ed. 1998 (ISBN 1-56512-132-5)), pp. 86–87 & n. [13] (author Mary Gabriel journalist, Reuters News Service). Also excerpted, differently, in Underhill, Lois Beachy, The Woman Who Ran for President: The Many Lives of Victoria Woodhull(Bridgehampton, N.Y.: Bridge Works, 1st ed. 1995 (ISBN 1-882593-10-3)), pp. 125–126 & unnumbered n.

“Arrest of Victoria Woodhull, Tennie C. Claflin and Col. Blood. They are Charged with Publishing an Obscene Newspaper.”. New York Times. November 3, 1872. Retrieved 2008-06-27. “The agent of the Society for the Suppression of Obscene Literature, yesterday morning, appeared before United States Commissioner Osborn and asked for a warrant for the arrest of Mrs. Victoria C. Woodhull and Miss Tennie …”

Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly (1870)

Wheeling, West Virginia Evening Standard (1875)

“Victoria Martin, Suffragist, Dies. Nominated for President of the United States as Mrs. Woodhull in 1872. Leader of Many Causes. Had Fostered Anglo-American Friendship Since She Became Wife of a Britisher …”. New York Times. June 11, 1927. Retrieved 2008-06-27.